Imagine this.. It’s late, and your deadline is inching closer. You’ve been staring at a blank page for hours. Finally, you turn to an AI chatbot for help, and on queue, it generates a perfectly crafted response… that’s completely incorrect. We all know this feeling. This moment of digital betrayal, powered by artificial intelligence (especially LLMs), is called a “hallucination.”

But what if these aren’t just random glitches? What if they are a feature, not a bug? What if the very way we train and evaluate our most advanced AI models is actively teaching them to lie to us or hallucinate like they do?

As per a recent research paper, “Why Language Models Hallucinate” by Adam Tauman Kalai and his team at OpenAI and Georgia Tech: this isn’t just another technical analysis. It’s a wake-up call for the entire AI community, from developers to end-users. They argue that hallucinations aren’t some ambiguous happening; they are the natural, statistical outcome of a flawed process. And to fix them, we can’t just rework the code; we have to change the way we work with LLMs.

What causes LLM hallucinations?

To understand why LLMs hallucinate, we need to go back to the point where it all starts, basically, the LLM “schooling” point. The paper makes a powerful analogy: think of a slightly confused student taking a hard exam. When faced with a question they don’t know, they might guess, or even bluff, to get a better score. But they’re not doing this to deceive; they’re doing it because the exam evaluation system rewards it.

This is exactly what happens with our LLMs. The problem isn’t just one thing; it’s a two-stage process that inevitably leads to the hallucinations in LLMs. Let’s understand both these steps:

Step 1: The Pre-Training

The first stage is pre-training, where a model learns the general patterns and distributions of language from massive text data. The most interesting insight from the paper here is its connection of this generative process to a much simpler concept: binary classification.

Imagine a simple, two-question problem for an AI:

- Is this a valid, factual statement? (Yes/No)

- Is this an incorrect, hallucinated statement? (Yes/No)

The researchers show that a model’s ability to generate valid statements is directly tied to its ability to solve this simple “Is-It-Valid” (IIV) classification problem.

In fact, the generative error rate (which determines how often it hallucinates) is at least double the rate of misclassification in this binary test.

Now this is a really powerful result! This just means that we can stop labelling hallucinations as some foreign or new phenomenon. In fact, we should start to see them as the same old, well-understood, and sort of expected “errors” that have plagued machine learning since the start of time.

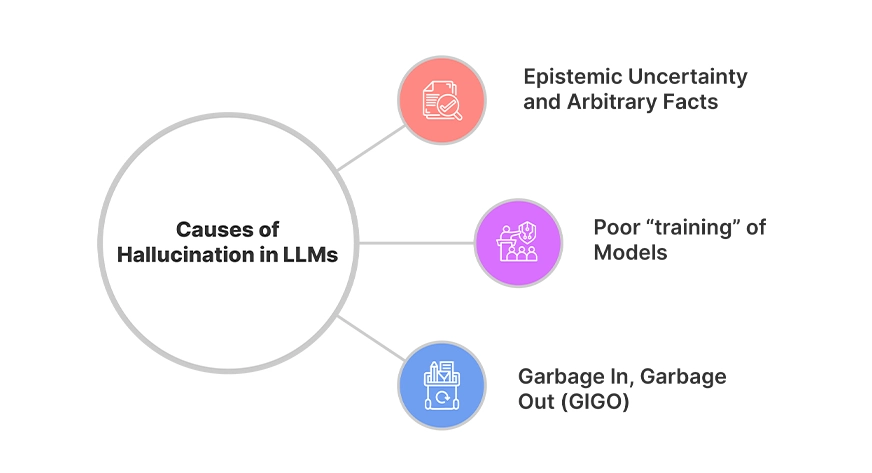

According to the paper, three main factors contribute to this:

- Epistemic Uncertainty and Arbitrary Facts: Some facts have no discernible pattern. For example, a person’s birthday is a random fact. If the AI sees a particular birthday only once in its massive training data, it has no way to “learn” that fact. So, when asked for it again, it’s forced to guess based on what’s statistically plausible. The paper states that if 20% of birthday facts appear only once, you can expect the model to hallucinate on at least 20% of those facts. This is pure statistical pressure, not a failure of logic.

- Poor “training” of Models: Sometimes, the model simply hasn’t learned the “rule” for a task. During its training process, a model is trained to understand and build logic on its own. The paper gives an example of an LLM struggling to count the number of “D’s” in the word “DEEPSEEK,” giving various incorrect answers. This isn’t a lack of data, but a failure of the model to properly apply the underlying logic.

- Garbage In, Garbage Out (GIGO): Training data, even when cleaned and prepared properly, is not perfect. It contains errors, misinformation, and biases. The model will, naturally, replicate these. While post-training can reduce some of this, like conspiracy theories, it doesn’t eliminate the fundamental problem.

The conclusion from this first stage is stark: even with pristine data, the statistical nature of pre-training makes some degree of hallucination unavoidable for a model that’s trying to be a general-purpose language generator like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Mistral.

Step 2: The Post-Training

So, if pre-training creates a tendency to err, shouldn’t the modern post-training techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) be able to fix them? The paper provides a very unexpected revelation for this: These techniques can’t fix these problems, because the very systems that are used to evaluate the LLMs actually reward the wrong behavior!

Remember the student analogy that we discussed above? They might know that answering “I don’t know” is the honest response, but if the exam gives zero points for a blank answer and one point for a correct one (even if it’s a lucky guess), the choice is clear: the best choice is to always guess. Since here they will always have a “chance” to score.

As per this research paper, this is a “socio-technical” problem associated with all LLMs. Most of the dominant benchmarks that models are judged on, the ones that fuel the public leaderboards and drive progress, use a simple binary scoring system. So the output for them is black or white. Meaning that a response is either correct or it isn’t. An “I don’t know” (IDK) response, or any other expression of uncertainty, is scored as zero.

To understand this, take the following example from the research paper. Suppose there are two models: Model A and Model B.

- Model A is a “good” model that knows when it’s uncertain and responds with “IDK.” It never hallucinates.

- Model B is the same as Model A, but it always guesses when it’s unsure, never admitting uncertainty.

Now, under a binary scoring system,

Model B will always outperform Model A. This creates an “epidemic” of penalizing uncertainty, forcing models to behave like overconfident students on a high-stakes exam. What is the result of this? Hallucinations persist, even in the most advanced language models. Essentially, the system we built to test honesty is actively teaching models to lie.

How can we avoid Hallucinations?

The paper is not all gloom; in fact, it brings in hope. The researchers propose a “socio-technical mitigation” that doesn’t require a fundamental AI breakthrough, but a simple change in human behavior. Instead of introducing new and more complex “hallucination-specific” evaluations, we need to modify the existing, widely-used benchmarks that dominate the field.

Their core idea is to improve the existing scoring system to reward uncertainty. Instead of a binary correct/incorrect, we should introduce a “third option”. This could take the form of:

“Giving credit for a correct “IDK” response when the model truly doesn’t know.”

Implementing “behavioral calibration”, which means the model learns to provide the most useful response for which it is at a certain “predefined” confidence level. This teaches the AI to be honest about its knowledge boundaries.

The paper argues this is a simple, practical change that can fix the misaligned incentives. When being honest stops being a losing strategy on the leaderboard, models will naturally evolve to be more trustworthy. The goal is to move from a system that rewards guessing to one that rewards accurate self-assessment.

Conclusion

This research paper peels back the layers of one of AI’s most persistent problems. It shows us that LLM hallucinations are not some mysterious, untraceable ghost in the machine. They are the predictable outcome of a system that rewards overconfidence and penalizes honesty.

This paper is a call to action. For researchers and developers, it’s a plea to rethink evaluation benchmarks. For leaders and professionals, it’s a reminder that a perfect-sounding answer is not always a trustworthy one. And for all of us, it’s a critical insight into the tools shaping our world.

The AI of tomorrow won’t just be about speed and power; it will be about trust. We must stop grading them like students on a multiple-choice test and start holding them to a higher standard, one that values the words, “I don’t know,” as much as the right answer. The future of a reliable and safe AI depends on it.

Read more: 7 Strategies to Mitigate Hallucinations in LLMs

Frequently Asked Questions

A. Because of the way they’re trained and evaluated. Pre-training forces them to guess on uncertain facts, and post-training rewards overconfident answers instead of honest uncertainty.

A. No. They’re a statistical outcome of flawed training and evaluation systems, not accidental mistakes.

A. Imperfect or rare data, like a unique birthday, creates epistemic uncertainty, forcing models to guess and often hallucinate.

A. Because benchmarks penalize “I don’t know” and reward guessing, models learn to bluff instead of admitting uncertainty.

A. By changing evaluation benchmarks to reward honest uncertainty. Giving partial credit for “I don’t know” encourages models to calibrate confidence and reduce LLM hallucinations.

Login to continue reading and enjoy expert-curated content.